The PR of Women’s Pain

Published on December 16, 2025, at 3:00 p.m.

by Emma Breithaupt

One in five. 20 percent. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), that’s how many women in the United States reported being mistreated during their pregnancy and childbirth experience in 2023. Women are absolute powerhouses when it comes to pain, but they shouldn’t have to be. For decades, women have been deemed unreliable narrators of their own experiences. Public perception has amplified this mantra, shaping provider views of women’s bodies and their pain. It is a communication problem as much as it is a medical one.

From past to present

Childbirth isn’t an experience that should be taken lightly. For some mothers, it can be an essentially painless one with attentive care and advocacy. For others, it can be traumatic, leaving them unheard with little to no support. A study conducted by the National Institutes of Health in 2016, which included 36 women, found that those who experienced traumatic births often received no follow-up from hospital obstetric or midwifery staff.

The conversation about women’s pain isn’t just one specific incident. It indicates a larger systemic problem that is rooted in academic research. Dr. Kathleen Rice, a contributor to the 2024 National Institutes of Health study on Gendered Worlds of Pain: Women, Marginalization, and Chronic Pain, found that pain in marginalized women is constantly dismissed. “I am certainly aware that there is more public discourse around Black women’s pain being minimized and ignored in perinatal care contexts. There is also a growing public conversation about women who receive inadequate pain relief during C-sections,” Dr. Rice says. This opens up a larger conversation about women’s pain management in general. “The research that I have done with my collaborators shows that women with pain navigate very gendered care roles and responsibilities that make living with their pain more difficult. This work is often unseen, and therefore unacknowledged by both the biomedical establishment and the general public,” says Dr. Rice. “It’s clear that media and cultural messaging reinforce ideals about good motherhood, good wifehood and the emotional labour that women should perform that pose challenges for women with chronic pain.”

To go even further back in history, birth was constantly shaped by a misguided public perception that overlooked women’s voices. While patient care was discovered and modified between the late 19th century and the mid-20th century, to this day mothers continue to feel neglected. A.J. Bauer, a historian, ethnographer and former journalist who now serves as an assistant professor in the Department of Journalism and Creative Media at The University of Alabama, researches the ways media narratives shape public understanding of social and political issues. He believes that there are individuals who have an inclination to not take women’s pain seriously. “This is obviously a very ludicrous and misogynistic thing because childbirth requires a lot of pain management.” This is portrayed in many pieces of media as well.

“There’s no medical study that women are weaker than men, these are all cultural norms conveyed via social media, film or T.V. Realistically, there are considerable varieties with pain thresholds. Other types of chronic pain in women are also understudied due to the assumption that it is all in their heads.” Societal responses like this influence not only research and treatment but also public perception around childbirth. The Retrievals Podcast echoes this, describing the ongoing dismissal of women’s pain in medicine. Several women in the podcast describe their mistreatment in a fertility clinic and how it affected them in the long run. Words like “too much pain”, “uncertainty”, “mistrust” and “frantic” seem to stick out on the first listen.

The interviews

Two mothers were interviewed about their childbirth experiences and the challenges they faced. Their names will be kept confidential for anonymity. Mother A, a first-time mom, gave birth in 2003 to a baby girl via emergency cesarean section (C-section). She also has a diagnosis of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) and an autoimmune disease, which can increase pain during childbirth due to joint instability and inflammation. Patients dealing with these types of disorders can feel pain differently. She remembers the experience like it was yesterday. From the beginning of labor, her pain was not adequately managed. Her regular OBGYN wasn’t on call, and when the epidural failed, nothing eased the pain the way she had been told to expect. She asked for repeated consults and other pain-management options, but no one followed through. Mother A endured 27 hours of pain. “I kept saying something was wrong, but I was treated like a typical patient even though my body wasn’t reacting like one. Every time I asked for help, I was brushed off and no one took my concerns seriously. A nurse told me, ‘Honey, that’s just part of childbirth.’” She and the baby began to show signs of distress, ultimately requiring an emergency C-section. “I didn’t feel heard. I was told that anxiety made things worse, and not to worry. We [as a society] are training women to ignore their pain to the point of putting their health at risk,” said Mother A. She felt that her concerns about pain weren’t taken seriously. “In talking with lots of women over the years, it’s clear that women don’t fake being sick—we fake being well. We smile through pain because we’ve learned to push through it, and that can make it too easy for our symptoms to be dismissed.” Her experience reflects the reality that the misrepresentation of women’s pain is an issue.

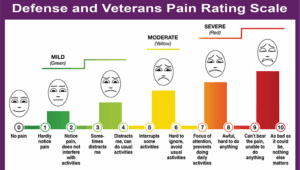

“The most important thing I’ve learned in dealing with chronic pain issues is that getting the care you need comes down to self-advocacy and clear communication. For example, the Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale, which pairs numbers with short, plain-language descriptions of how pain affects your ability to function, takes the basic ‘faces’ scale and turns it into a real conversation. It makes doctors actually talk with you instead of judging your pain by how you look,” she said. “This has taught me that giving people a way to clearly describe what they’re feeling truly changes everything. But that only happens when both doctors and patients are educated with clear PR messaging, simple materials and communication tools that help people put their symptoms into words.” If people can’t see the pain women go through and communication fails, even the strongest voices can feel unheard.

Mother B also had a C-section with her third pregnancy, although this one was a bit more planned. In 2010, she gave birth to twins, one boy and one girl. At the beginning of her pregnancy, she told her obstetrician that she wanted to avoid a C-section if possible. Months later, it was decided that both would need to delivered via C-section. “I was nervous, for sure. My obstetrician was a male, and I don’t remember there being conversations about what was going to happen.” Mother B said that some of her medical advice came from her friends who had already had children. “Before I gave birth, one of the girlfriends told me that I would get a terrible headache a week after your C-section from the epidural. I thought, whatever. That can’t be real! And sure enough, a week later, I had the worst headache I had ever had in my life.” Not feeling prepared is a pretty common factor when it comes to C-sections.

“I think a lot of female medicine is just a woman telling another woman, and it shouldn’t have to be that way,” said Mother B. “I—on purpose—decided to choose a pediatrician who was a woman because I wanted a mother who had been awake at 3 o’clock in the morning trying to nurse a baby.” She thinks that the younger generation will be able to fight for better responses to women’s pain. “Teaching younger generations about being more self-aware and advocating for themselves is so important. That alone will change the landscape. We need to value each woman’s opinion and experience instead of smiling, nodding our heads and suffering in silence.”

Until professionals accurately represent women’s pain in both media and healthcare communications, they will continue to fail them.