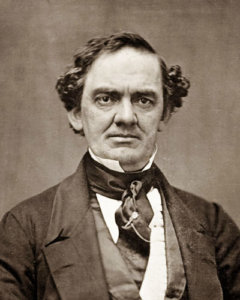

P.T. Barnum: How ‘The Greatest Showman’ Would Survive in PR Today

Published on April 25, 2018, at 11:10 p.m.

by JoAnne Wadsworth.

As the performers break into a last, heartwarming musical number, you settle back into your chair, satisfied. This movie has been great — full of true love, tear-jerking moments and … wait. What?

You drop your last handful of popcorn as police officers swarm the circus stage and haul P.T. Barnum off in handcuffs. With a final crash of cymbals, the screen goes black, the credits roll and stunned silence fills the theater. It’s palpable.

Don’t worry. If “The Greatest Showman” had really ended that way, it wouldn’t be so popular. Word-of-mouth has sent the movie on its way to being one of the top-grossing musicals of all time. In fact, attendance increased instead of decreasing as the weeks passed, leaving critics scratching their heads. The show’s romantic take on Barnum’s life is fictional at best, but most viewers (except for the sticklers for historical accuracy) loved it.

This fictional version of Barnum already dropped into our world via the big screen — but what would happen if the real Barnum, a huge influencer in the development of modern public relations, dropped into the world of a PR professional right now? Would police officers haul him off for false advertising?

Well, maybe.

The crimes

A large majority of the king of humbug’s antics could be seen as crimes today.

The Federal Trade Commission exists to protect consumers from false advertising claims. Title 15 of the U.S. Code lays out the consequences for lying about a product or service to consumers. Lie more than once, like Barnum did, and you could be fined $10,000 and/or thrown in jail for up to a year.

Barnum got his start in show biz with a perfect example of what would now be called “fake news.” He bought an old African-American slave woman named Joice Heth and taught her a routine, advertising her as George Washington’s 161-year-old nursemaid. Heth was actually in her 80s, and had no ties with Washington. When she died, a public autopsy (Barnum charged admission) proved the claims false, but by that point Barnum had already made a pretty penny. He just smiled and claimed he’d been hoodwinked.

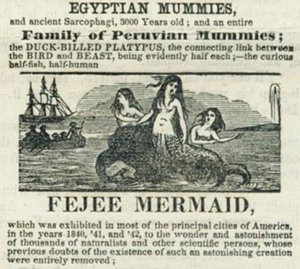

The “Feejee Mermaid” gained the next big wave of publicity. Barnum’s advertisements showed a beautiful woman, supposedly found somewhere in the tropics. In reality, the “mermaid” was a monkey carcass stitched to a fish tail. Ticket sales boomed.

The “Cardiff Giant” grew out of someone else’s lie. Workers digging in Cardiff, New York, claimed to find the petrified body of a 10-foot-tall man. The giant was actually made of gypsum, and showman David Hannum began to earn a profit by charging admission for his “biblical giant.” When Hannum refused to sell his giant to Barnum, Barnum made his own “Cardiff Giant” statue and claimed that the original was a fake. Newspapers ran the story, and Barnum’s popularity increased.

Dick Martin, author of a textbook on PR ethics and member of the board of trustees at the Museum of Public Relations, compared many of Barnum’s falsehoods with what happens on the internet today.

“There are all kinds of things on the internet that are patently false, but people eat them up because they support some deep belief that they have,” Martin said. “Barnum would have been a master of using the internet. He knew exactly how to do it and he always gave himself an out.”

Barnum wasn’t necessarily afraid of the law — he was arrested three times for libel during his stint as a newspaper publisher. But today’s highly regulated communications environment would be even less accommodating. He’d probably end up in some messy legal battles, if not prison. He’d also be kicked out of any self-respecting PR association, as the first item on most professional ethics codes is “be honest.”

The gray area

Not all ethical violations are necessarily illegal.

Joseph Ogden, co-author of a top-selling textbook on PR strategy, said that ethics are the foundation of trust between people and organizations. As PR professionals, we rely on transparency to maintain that trust with our publics.

For Barnum, ethics were foggy at best. Once, he invited the public to a private island to watch a “free” event where cowboys hunted live, wild buffalo. Over 20,000 people came to the island only to find a few scrawny, underfed buffalo that startled and ran away. Though Barnum publicized the event as free, he cut a deal with the ferry owners to get a piece of every person’s boat fare to the island.

When the public began to doubt Joice Heth’s age, Barnum wrote an anonymous letter to a local newspaper claiming that she wasn’t just a fake, but a robot as well. People came to see for themselves and ticket sales got a sizable boost.

Both of these instances are ethically ambiguous and violate trust.

“I think in most cases anything written anonymously is borderline, if not totally, unethical,” Ogden said. “There’s no source, so nothing can be validated, and that doesn’t square with building trust with any organization.”

Martin said Barnum found much of his success by manipulating people’s emotions.

“He understood what their prejudices were, what their deepest resentments and beliefs were, and he pandered to them,” Martin said. “[His attractions] promoted and perpetuated prejudices and biases.”

As social media continues to change the communications world, PR professionals must be more and more careful with their messaging. Recently the International Association of Business Communicators added a new point to its ethics code: “Professional communication is in good taste.”

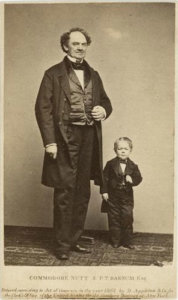

Barnum charged admission to Joice Heth’s autopsy. He made his fortune by featuring “oddities” like the dwarf Tom Thumb, Siamese twins and fat ladies. Today, those actions would be seen as not only insensitive but condemnable.

“You would get completely ridiculed and raked over the coals on social media for that,” Ogden said. “You would just be obliterated by people because it is in poor taste, and it’s not professional in any way.”

The genius

Despite Barnum’s outright lies and shady methods, he displayed an astounding knack for publicity.

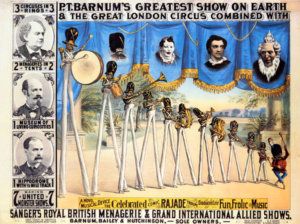

When the Brooklyn Bridge was newly finished, Barnum proposed to “test if it was safe for the public” by leading his circus elephants across. His request was denied at first, but he got his wish through persistence. On May 17, 1884, he brought 21 elephants and 17 camels across the bridge, led by the famous elephant Jumbo. It astounded onlookers and paved the way for PR publicity stunts today. The scene was so memorable and effective that it was still getting Barnum press coverage 120 years later, in 2004, when it made the cover of The New Yorker.

As another staged event, Barnum plowed his front yard with a circus elephant to get the attention of commuters on the passing trains. He plowed the 6 acres more than 60 times before he decided he’d earned enough coverage.

“I believe hugely in advertising and blowing my own trumpet, beating the gongs, drums, etc., to attract attention to a show,” Barnum said in a private letter.

He once thanked the press for almost every dollar he possessed, and he was right to do so: At a time when the census estimated the United States population to be under 32 million people, Barnum’s museum hosted 38 million visitors in a 24-year period. What PR professional today can claim such a ratio of engagement?

The greatest showman may have been narcissistic and risk-inclined, but he utilized incredible creativity and seized every opportunity for publicity.

“You don’t, by being a shrinking wallflower, get on the front page of The New York Times,” Ogden said. “He was the Hulu and Netflix of his day. He was entertainment for people. And I think it’s amazing the ideas that he came up with.”

Dodge the shadow, catch the vision

In a day and age where PR is about relationships and ethics revolve around transparency, it’s easy to disparage Barnum. He was a conniver, he generated fake news, and he was unethical more often than not. If he dropped into the world of a PR professional today, he would probably lose all his credibility and possibly his job. However, though debates rage about his character, his legacy lives on through his ideas. As PR professionals, we must avoid Barnum’s ethical pitfalls while pursuing his streak of genius.

“I think the most important thing to learn from Barnum is that you don’t have to do things the way that everybody else does them — that creativity and ingenuity can set you apart in your field,” Ogden said. “You could learn so much about how to position an issue just by studying P.T. Barnum’s life. We must learn how to think about things in a totally different way, because our biggest challenge in communications today remains getting attention. Cutting through the clutter. And P.T. Barnum did that better than anybody in history.”